Blog

Beethoven, Egmont and the Ideals of the French Revolution

1/14/2026

Egmont to Dallaire

Somewhere deep in the extensive oeuvre of American conductor Kent Nagano lies a gem seemingly undiscovered by the internet; unreviewed, scarcely played on Spotify or other streaming services. By its cover, Beethoven - Ideals of the French Revolution doesn't stand out in the vast field of Beethoven renditions. The virtually perfect musical execution that it is, too, does not necessarily set it apart . Where it is unrivalled, is in the rediscovery of the story behind Egmont - the hero of liberty in Goethe's story that inspired Beethoven. Nagano interweaves the music of Egmont and other aptly chosen individual pieces with narrative from the memoirs of Canadian general Roméo Dallaire, who is painted as Egmont's contemporary counterpart through Beethoven's music. Behind this seemingly far-fetched connection, lies a deep and powerful analogy that, through listening, slowly reveals itself.

Beethoven's Egmont

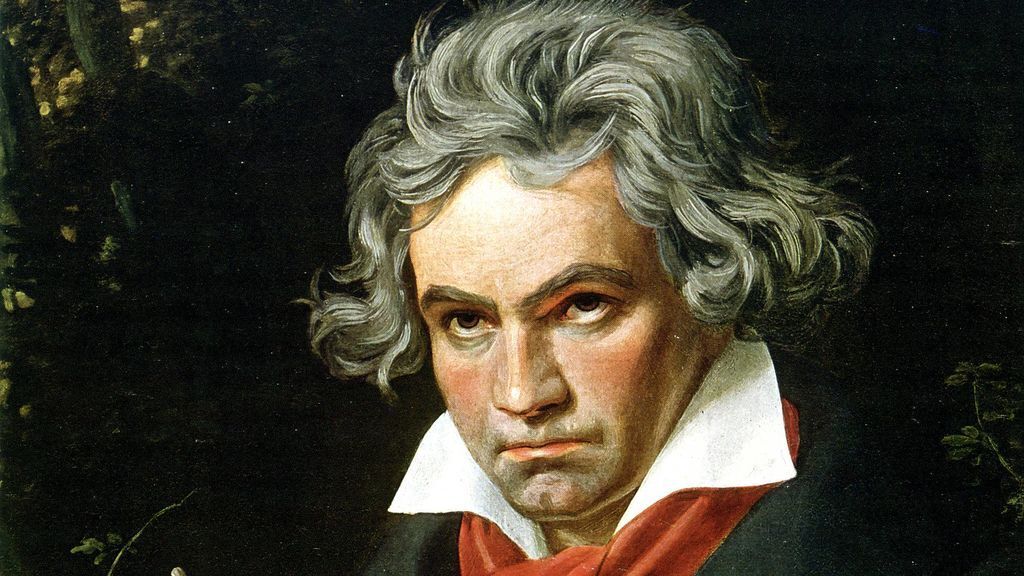

Egmont, Op. 84 is Ludwig van Beethoven's set of incidental music pieces for the 1787 play of the same name by Johann Wolfgang von Goethe. Paraphrasing from Wikipedia, the subject of the music and dramatic narrative is the life and heroism of nobleman Lamoral, Count of Egmont from the Habsburg Netherlands. It was composed during the Napoleonic Wars. In the music for Egmont, Beethoven expressed his own political concerns through the exaltation of the heroic sacrifice of a man condemned to death for having taken a valiant stand against oppression.

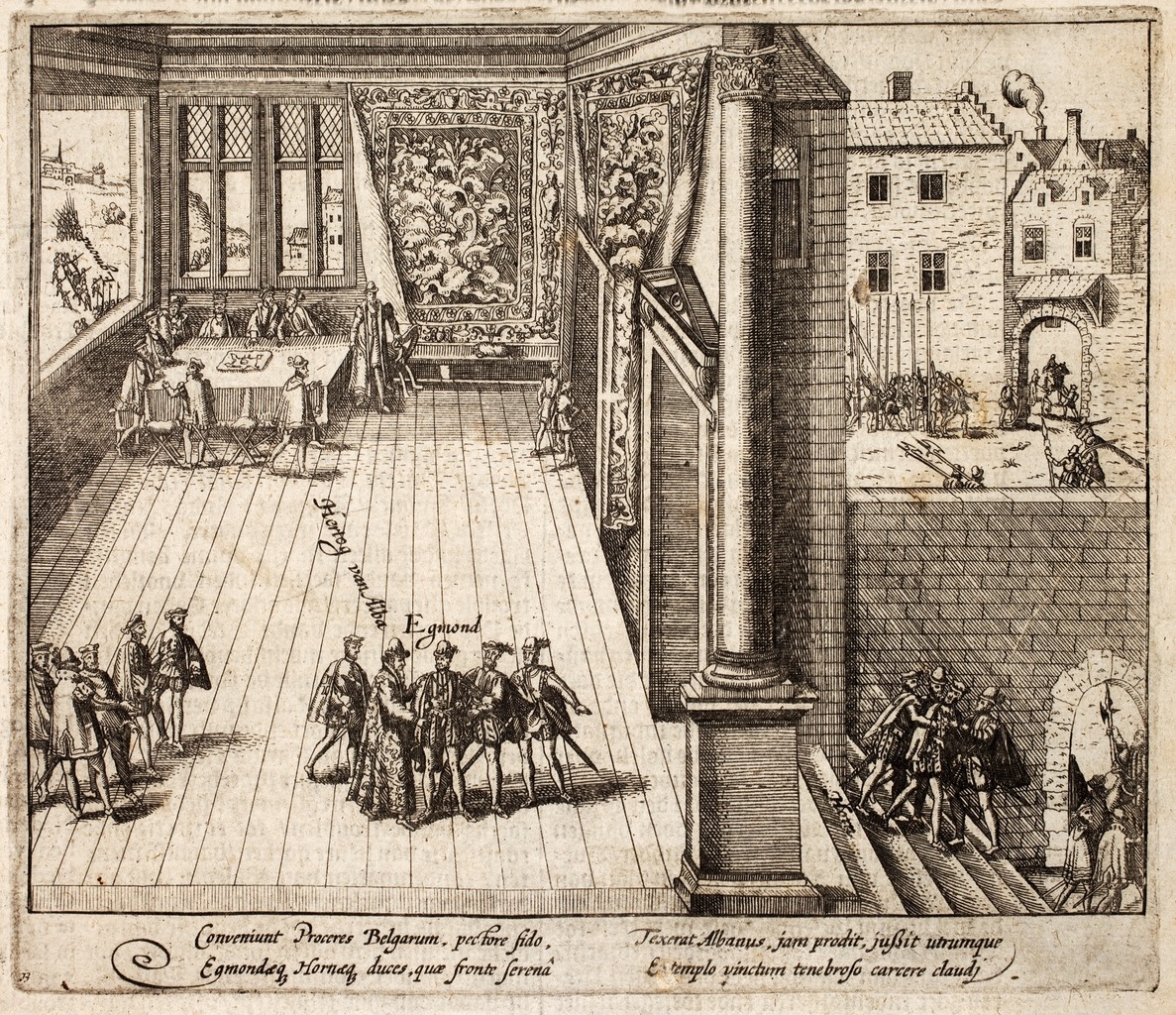

The titular main character is loyal to the Spanish crown and the Catholic faith, but champions tolerance of Protestants and other non-Catholics. The story pits him against the brutal Duke of Alva, who is sent to repress Protestant rebellion in the Habsburg Netherlands. In 1565, Egmont was sent to Madrid to plead for clemency for persecuted Protestants, but was received with apparent cordiality while the King secretly sent the Alva to crush all resistance with an iron hand. Egmont proves to be no match for Alva's scheming and is sentenced to die, though at the conclusion he has a vision of the eventual triumph of freedom. The play centers on Egmont's arrest, his isolation as allies desert him, and his execution—a martyrdom that emboldens the Dutch resistance against Spanish rule.

The Duke of Alva arrests Egmont and Horne - Pieter Christiaensz. Bor, 1621

The Duke of Alva arrests Egmont and Horne - Pieter Christiaensz. Bor, 1621

The mainstay of Beethoven's incidental music is the Egmont Overture, the rest of the incidental music commonly receives less attention and is not typically part of Beethoven concerts and compilations. All parts are represented on the first part of this album, titled The General. The second part consists of highlights from The General but without narrative, along with an excellent version of Symphony in C Minor. I'll leave a review of the musical subtleties of Nagano's version of them to more seasoned Beethoven critics. To less trained ears like mine, it is among the best. Alongside symphony orchestra and soprano, it is sometimes performed with a narrator, and this is where Nagano's creative liberty shines.

A contemporary Egmont

The narrative that Nagano decided to use instead of Goethe's in The General is that of Roméo Dallaire. A now retired Canadian military officer who became internationally known for his leadership of the United Nations Assistance Mission for Rwanda (UNAMIR) during the Rwandan genocide in 1994, one of the most horrific humanitarian disasters of the 20th century.

In early 1994, as the genocide unfolded, Dallaire made urgent appeals to the United Nations for additional troops and resources to help stop the mass killings. Despite his warnings and pleas, the UN Security Council voted to reduce UNAMIR's force from 2,500 to 270 troops, leaving Dallaire and his depleted command unable to prevent the slaughter of nearly one million Rwandans over approximately 100 days.

Dallaire's experience profoundly traumatized him. After returning from Rwanda, he struggled with severe post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), depression, and attempted suicide multiple times. Recovering (insofar possible) from these horrible experiences, he has become a vocal force for humanitarian intervention and genocide prevention.

Since retiring from the military, Dallaire has been active as an author, speaker, and advocate for genocide prevention and human rights. He has continued to work on issues related to international responsibility to protect, child soldiers, and mental health awareness. His memoir Shake Hands with the Devil is the source of the narrative fragments used on the album.

Parallels

There are sufficient differences between Dallaire and Egmont to prevent any direct comparisons from appearing. As far as I can tell, Nagano has been the first (or only) one to (publicly) connect the two. There are some striking parallels in the two stories worth exploring, and Nagano encourages us to do so through Beethoven's music.

Egmont, Overture

Egmont Overture has been described as heroic, fierce but also dark and ominous, and Nagano's version brings these elements out in full. The story of Egmont is not one where liberty triumphs, and perhaps Nagano felt too that it is precisely the tention of ideals and reality that Beethoven was so brilliant at capturing.

The importance of freedom found in this score has been interpreted as a projection of Beethoven onto the character of Egmont, due to his social confinement because of his deafness and unmarried life. Beethoven also felt strongly about the political will of Napoleon and other political figures to establish a centralised order around the time he finished Egmont. Austria declared war on France on 9 April 1809, and Napoleon's troops had besieged and taken the city of Vienna. We have no shortage of reasons why Beethoven fervently cherished freedom.

Leonore Prohaska - Funeral March

Marie Christiane Eleonore Prochaska was a German woman who, disguised as a man, fought in the Prussian army against Napoleon during the War of the Sixth Coalition and died from her wounds in 1813. Her deeds became legendary soon after, and she was often compared to Joan of Arc. Beethoven wrote incidental music for a drama about her life written by Friedrich Duncker. Its manuscript has been lost, but we have some excerpts from Beethoven's score. For example, this segment from the work preceding the Funeral March.

Du, dem sie gewunden,

es waren dein zwei Blumen fur Liebe und Treue.

Jetzt kann ich Totenblumen dir weih’n,

doch wachsen an meinem Leichenstein

die Lilie und Rose auf’s neue.

Source: lvbeethoven.org

Prohaska's death is dramatised to be noble. Death also is not ugly, for on the gravestone, "the lily and rose grow anew." Could Nagano then paint a starker contrast than to that of Dallaire.

But no. Here, death was not noble. As the radio stations burned on embers of division, work gangs turned into killers. Some of the poorest people on earth, neglected and hopeless, slashed at their neighbors.

Egmont, Nr. 3, Entractre

Some hope sparks in Dallaire at the sight of the horror. "I could do something!" Moral clarity is something we see in both Egmont and Dallaire, two men who stepped forward as moral voices when institutional authority was failing the people.

I need help! (...) Enough men to cover the country! Equipment to jam the radio! And I need them now!

In both cases, however, their initial pleas fell to deaf ears.

I received nothing but a warning. I was not to get involved. (...) To inhuman behaviour came the inhuman response. Protect what's close to you, don't grieve for the rest.

Egmont, Nr. 7 & 8, Claras Tod & Melodrama

The death scene of Egmont's beloved, Clara (or Clärchen), is set to calmer but barely less ominous tones. This is the moment of quiet despair in Egmont, where we hear Nagano bring out the brilliance of Beethoven once again. And in the following Melodrama (Nr. 8), comes a crucial moment of introspection and realisation for Dallaire.

I was one human being. What use were my thoughts? And my feelings? Care? Sympathy? And what, regret? What use were the illusions I'd had? Peace. (...) Now, I had to face the truth. I was the token commander of token troops.

The subtle touch of military style drum fills is the perfect finishing touch to this dramatic piece. Here are two pieces among the least commonly played from Beethoven's works, of haunting beauty and emotion. Music that portrays humanity so true, its quality will be hard to match for another two hundred years.

Finale - Opferlied

The General closes with the aptly chosen Opferlied, which roughly translates as victim's song. This work from Beethoven's later life is set to Friedrich von Matthison's poem with the same title, which according to its words is a "prayer for all the seasons."

Die Flamme lodert, milder Schein

Durchglänzt den düstern Eichenhain,

Und Weihrauchdüfte wallen.

O neig ein gnädig Ohr zu mir

Und laß des Jünglings Opfer dir,

Du Höchster, wohlgefallen.

Sei stets der Freiheit Wehr und Schild!

Dein Lebensgeist durchatme mild

Luft, Erde, Feu'r und Fluten!

Gib mir, als Jüngling und als Greis,

Am väterlichen Herd, o Zeus,

Das Schöne zu dem Guten

Source: Hungarian National Philharmonic

The piece came together over several decades, an indication of just how important Matthison's poem was for Beethoven. Perhaps because of its final lines proclaiming the unity of the Beautiful and the Good, Beethoven's personal artistic and philosophical credo.

In English:

Give me, as youth and as old man,

By my father's hearth, O Zeus,

That which is beautiful to the good.

Egmont is executed, but ultimately a vision appears in which Freedom holds above his head a wreath of victory. Egmont's martyrdom, with that of Count Horn, and later the assassination of William of Orange, roused the Netherlands to a resistance that ended only with the complete throwing off of the Spanish yoke. While Dallaire survived, his testimony about Rwanda has become a catalyst for awareness about genocide prevention and the responsibility to protect—his voice, haunted by what he witnessed, has awakened global conscience in a way that passive success could not.

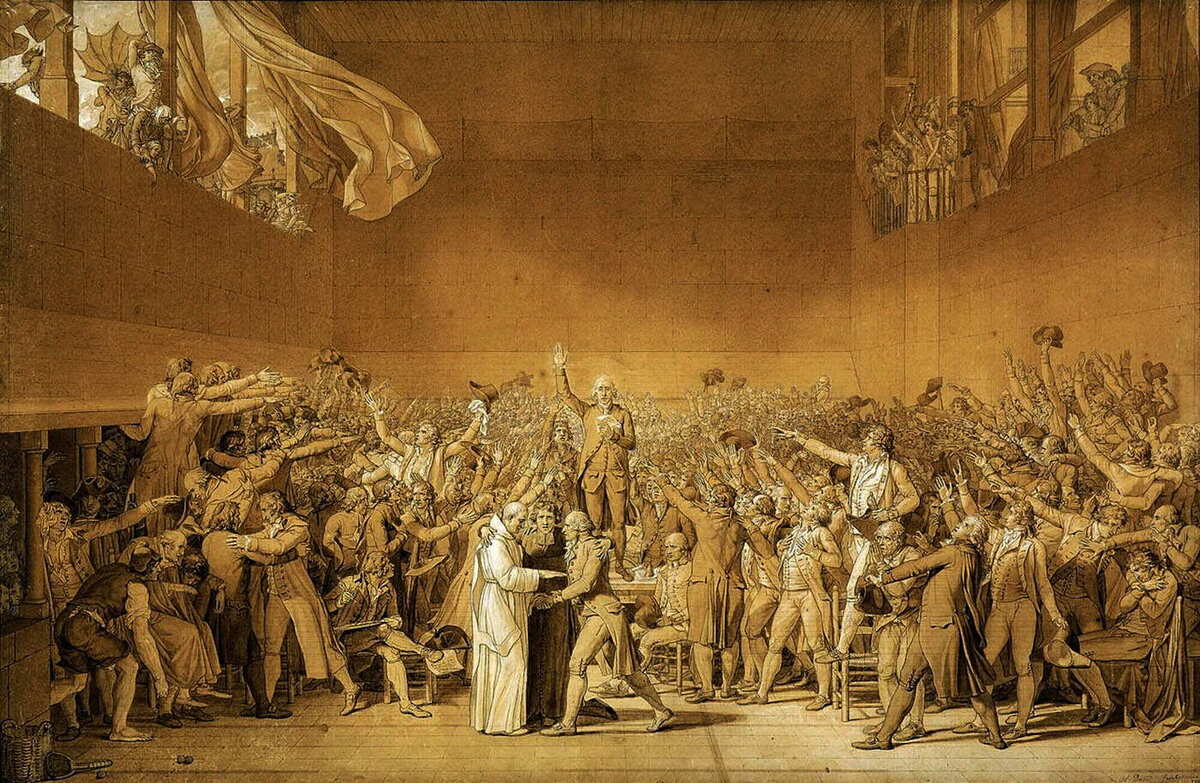

Ideals of the French Revolution

The title of the album prompts us to think. The French Revolution championed liberté, égalité, fraternité—liberty, equality, and brotherhood. These ideals imagined a world where reason would triumph over tyranny, where individuals would be protected from despotic authority, and where universal human rights would govern human relations. Do these ideals remain just that; ideals? The stories at hand certainly do not laud their equivocal success. On the contrary, it makes us suspect they remain tragically unrealised. Egmont and Dallaire become twin witnesses to this failure, separated by centuries but united in their experience of moral clarity meeting institutional indifference.

The Tennis Court Oath - Jacques-Louis David. It depicts one of the foundational events of the French Revolution.

The Tennis Court Oath - Jacques-Louis David. It depicts one of the foundational events of the French Revolution.

Nagano's genius is in using Beethoven—the supreme composer of human aspiration and transcendence—to hold this tension: the soaring Revolutionary ideals in the music stand in perpetual, heartrending contrast to the historical evidence that those ideals continue to be betrayed. The "ideals" in the title are not celebrated; they are interrogated, mourned, and held up as an indictment of continued human failure to honor them.

Further reading/listening

Egmont, Johann Wolfgang Goethe - Goethe's original work

We Wish to Inform You That Tomorrow We Will Be Killed with Our Families - Stories from Rwanda, Philip Gourevitch - An excellent account on the Rwandan genocide

Shake Hands With the Devil, Roméo Dallaire - Dallaire's own account of the events, source of the narrative on Ideals of the French Revolution

Revolutions Podcast season 3: The French Revolution, Mike Duncan - A great in-depth but engaging tour through the events of the French revolution. Other seasons are strongly recommended too.